The Salmon's Spin

Tractatus Ayyew

Book Two | Earthen Principle No. 2

1,946 words

Tractatus Ayyew

Book Two | Earthen Principle No. 2

1,946 words

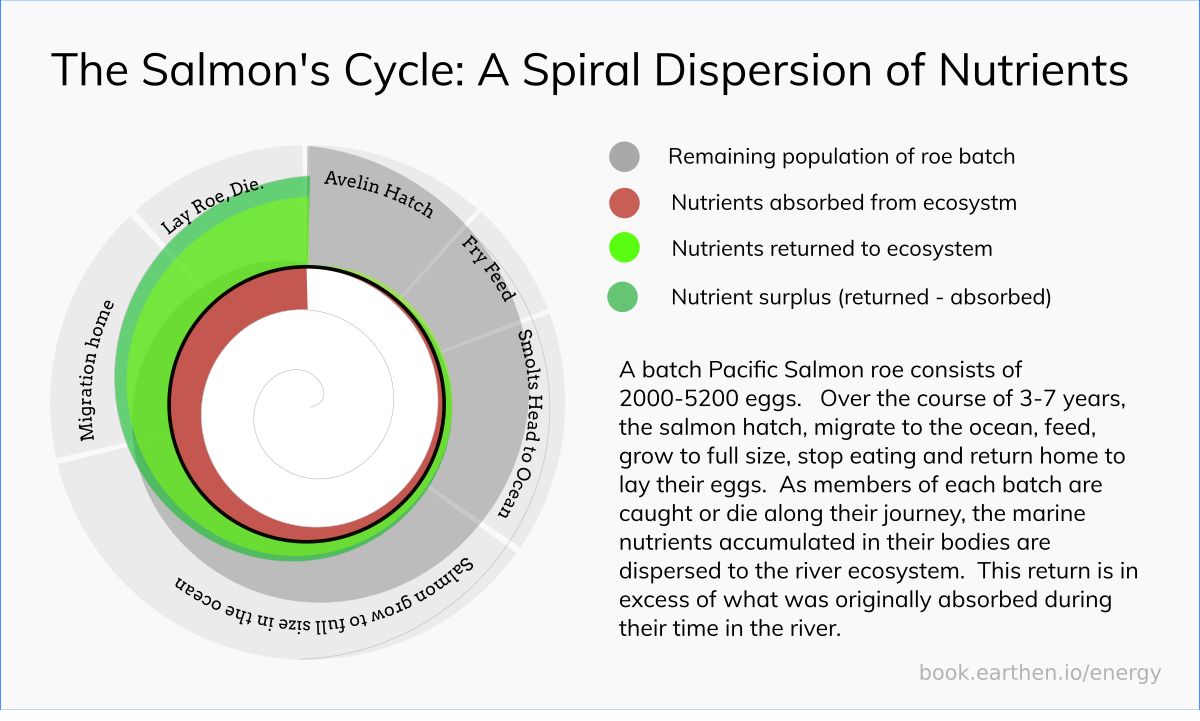

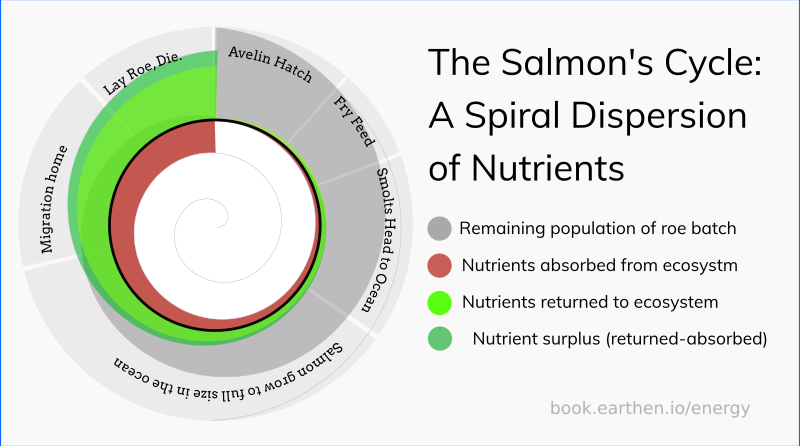

Thirteen thousand years ago, as trillion-ton ice-sheets retreated from North America's Pacific coast, barren desolation reigned. However, in the lingering glacial streams, the continent's revitalization had already begun. Proliferating river by river down the warming coast, the adventurous ancestors of today's salmon swan inland to deposit their eggs. Ever since, with each season, their energizing cycle has spun. Come Spring, the salmon roe hatch and emerge from the rocky river bed. The tiny fish gather their strength consuming insects and waterborne larvae. Come Summer, they set out on a journey to the ocean. Once arrived they feast on nutrient rich marine life. After several years, when they have reached their full size and strength, they are ready to head home. Come Fall, millions of salmon retrace their river route and an entire ecosystem revels in their return. Bears, eagles and humans gather for grand fishing feasts. Even the bugs partake! The remnants of consumed carcasses nourish the very insects upon which the salmon first fed. Meanwhile, those salmon that slipped by, continue to the waters where they were born. Using the last of their strength, they deposit their eggs in the gravel. The salmon then die; their decomposition a final nutrient gift to the river ecosystem that their roe will soon run.

OVER THE MILLENNIA, the Wet'suwet'en people of North America's Pacific coast have lived alongside the salmon's masterful management of energy. Observing and learning from the salmon, the Wet'suwet'en and their ancestors presided over the steady transformation of barren glacial desolation into what is today a biome teeming with life of all kinds. We too have much to learn from the salmon— and from the Wet'suwet'en. As we shall see, the way in which they patterned their lives upon the salmon’s outward spiral of energy provides a green path forward for us and our modern enterprises. Indeed, the geometric pattern that both the Wet'suwet'en and the salmon share, mirrors the energetic pattern by which Earth itself greened. This resonance provides us with the basis for our second Earthen ethic. Here, Earth's pattern of energy management, coupled with the Wet'suwet'en example of its cultural implementation, provides the foundation by which we must structure our enterprises to ensure that they are in fact green.

To begin, let us return once again to our planet's primordial origins and take a closer look at the particular pattern that characterizes Earth's energetic spirals.

As we saw in Plastic's stellar story, over the last four billion years, the energy of the Sun's relentless blaze coursed through Earth's cycles of geology, ocean and atmosphere. Driven by the rigid dictates of thermodynamics and guided by Earth's unique cosmological character, Earth's matter was churned by the ever arriving solar energy an the rhythms of Earth's spin, solar orbit and lunar companion. Out of these Earthen cycles, systems unfurled that ever better dissipated the Sun's energy. Steadily, configurations of matter organically emerged that gathered, stored, then dispersed energy ever outwards towards equilibrium.⁶⁶

Before long, the sun’s shine was being stored in complex, energy-dense molecules such as fats, proteins and carbohydrates that were interchangeable among cellular systems. As organisms lived and died, these nutrients were consumed and used by others. Gaining the energy of those before them, organisms reproduced and proliferated; each cycle steadily spinning nutrient energy outwards to other organisms within the shared space.⁶⁷

With countless life cycles spinning, collectives of organisms became systems unto themselves. Undulating to the rhythms the sun and moon these systems of systems then spun their energy upwards again. Steadily, nutrient energy was dispersed ever more effectively out across the planet's surface. From organism to ecosystem, from ecosystem to biome, energy spiraled ever outwards towards the enrichment of all.⁶⁰

And Earth’s once barren continents greened!

Just like ice age North America.

Over the last ten thousand years, the progression of age ice ravaged North America into a teeming biome, is a microcosm of Earth's own transition from barren to biosphere. Looking carefully at the role of the Salmon, we can see how the same energetic pattern played out-- and discern our second Earthen ethic.

Just as the Earth's cycles steadily spun the sun's energy out across the planet's surface, so too did the salmon cycles steadily spin nutrient energy out to its continental ecosystem.⁶⁸ And just as Earth’s outwards energetic spiral steadily greened its biosphere, so too did the salmon's outwards dispersion of nutrients relentlessly contribute to the enrichment of its biome— a common home for which countless other creatures could flourish.⁶⁹

As the life cycles of bears, bugs, eagles and humans prospered with each fall feast, the living of all intertwined and reverberated.⁷⁰. As the entire ecosystem thrived, the conditions for future salmon generations steadily improved-- furthering compounding and accelerating the enrichment of the entire biome. With the outwards distribution of energy hardwired into its lifecycle, Salmon became a cornerstone species in the inexorable enrichment of river and land.⁷¹

Looking at the contribution of the Salmon from this planetary perspective, we can see the Earthen pattern it embodies. Here we find our second Earthen ethic-- a principle of energy management that our keen green enterprises have much to learn from.

Just as the salmon and Earth tended their cycles towards the spin of energy outwards to all, so too must we intend and achieve with our own. Only when the intention and the result of our cyclical processes is the net-outwards distribution of energy, is this second Earthen ethic met. Only then can our enterprises be considered an ecological contribution— and green.

But, how exactly do we do this with our human process, projects and enterprises?

Here we have much to learn from the people, who themselves long learned from the Salmon— and whose ancestors presided over one of the most dazzling and incontrivertable ecological enrichments of the last ten thousand years.

For the Wet’suwet’en the example of the salmon was impossible to overlook. Among the multitude of creatures around them, the extremes of life and death of the salmon were by far the most dazzling. In their autumn run, the vitality and numbers of the salmon would make the waters boil only for them to die and decay en masse after laying their eggs. Each year they would observe the bears, eagles and bugs feasting upon the salmon. As they themselves feasted upon the salmon, the Salmon's great generosity and its success as a strategy were self-evident.⁷²

In this way, the Salmon were far more than food. From the Wet'suwet'en's kincentric view of the world, the salmon were also kindred creatures, ecological elders and respected teachers. Over the millennia the Wet'suwet'en learned from the Salmon. They wove the salmon's pattern of spiralling energetic distribution into their stories, traditions and values⁷³

In Wet'suwet'en tradition, the very first salmon caught each Autumn is shared with the entire the community or family unit. In this tradition, a morsel of the fish is meticulously distributed among each member, while each and every bone is taken back and returned to the river. This pattern is then followed in the seasonal harvest of tens of thousands of salmon. Only as much salmon required by each family is taken, while the vast majority are allowed to pass through to lay their eggs and be consumed by other creatures. What is caught is distribution among the community as needed, while all the bones are brought back to the water ⁷⁴. So ingrained is this spirit of dispersal, that in the Wetʼsuwetʼen language the very word for 'salmon' means 'everyone's salmon': it is impossible to speak of 'my salmon'.

For the Wet'suwet'en, this ethic culminates in the potlatch (a tradition shared with virtually every other first nation on the North West coast). In this seasonal ceremony, the community comes together to distribute items of value that had been accumulated. Everything from food, to blankets, to jewelery to currency are brought to be gifted at the ceremony.⁷⁵

Today, as our modern enterprises strive to go green, the Wet'suwet'en show us the way forward.

First and foremost is their non-dualistic kincentric understanding of social and ecological energy. Just as humans, animals, fish and plants are all kindred components of the ecological system that holds them, so too are the flows of human food, favors, debts, payments and transactions of all kinds held by the same energetic laws. For the Wetsuwetn, patterns of financial flow are not seperate or exceptional to the energetic patterns of enrichment or depletion that characterize ecological flows.

From this view we can better understand our human enterprises anew.

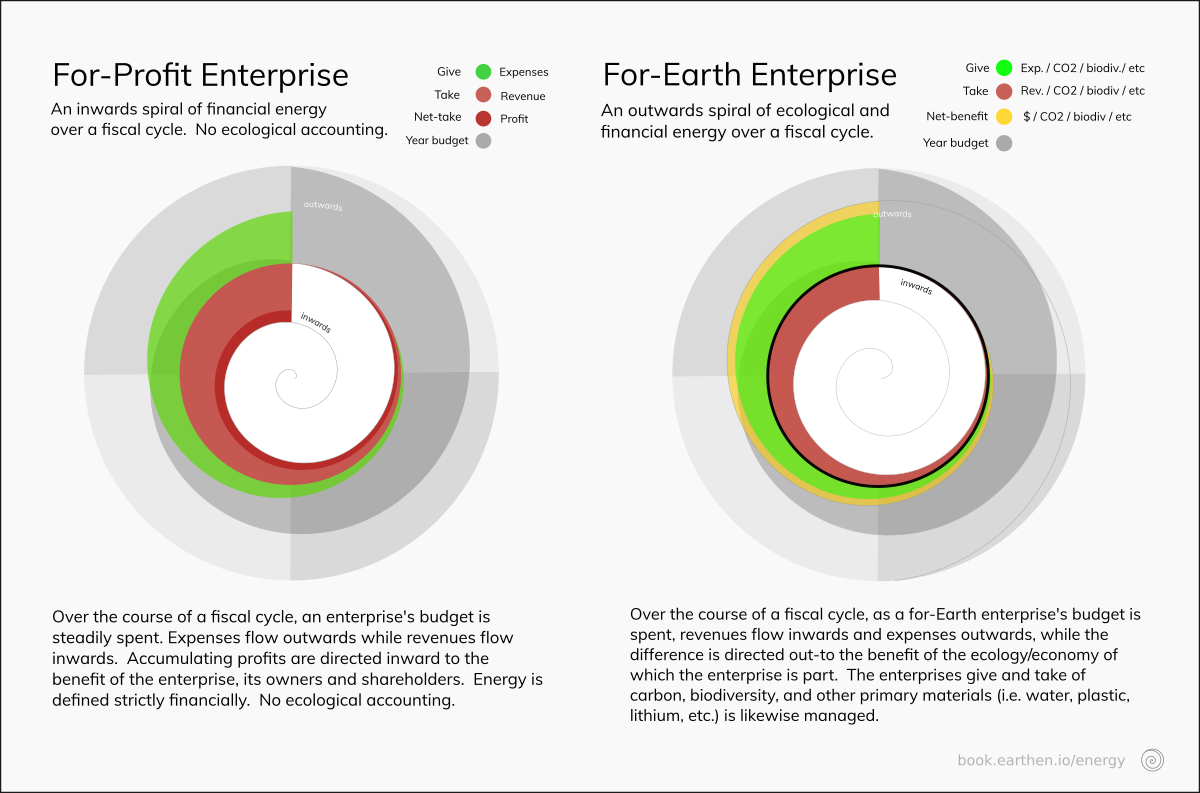

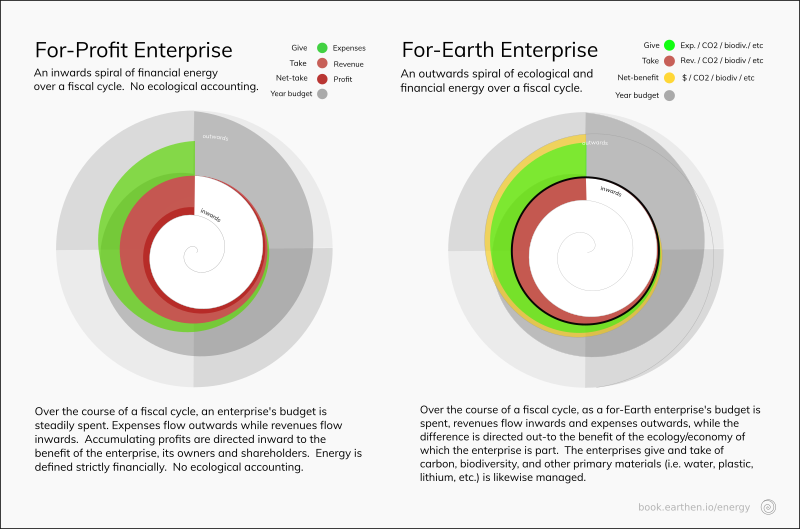

Whereas an organism manages its give and take of nutrients over seasonal cycles, an enterprises manages its revenues and expenses over fiscal cycles. Whereas energy flow through an organism in the form of carbohydrates and are stored as fats and protein, within an enterprise energy flows as currency and is stored as capital and assets.

Through these parallels, we can observe comparable patterns.

Whether it is an organism or enterprise, an ecosystem or an economy, as each system spins, their pattern of energetic give and take tends their cycles either inward our outward: towards the concentration of energy into themselves or outwards towards the dispersal of energy to their encompassing system.⁷⁶

When it comes to our human enterprises, their pattern of energy management is determined by the purpose for which the enterprise is established. The for of an enterprise determines how and why it receives revenues and expends expenses— as well as the how and why of its ecological give and take.

When it comes to an enterprises tendency to enrich or deplete, there is a singular preliminary determinate

Their founding intention.

Today most enterprises operate with the purpose of meeting human wants and needs— such as for the provision of products and for the delivery of services. However, many modern enterprises tend to be structured for a deeper reason. Namely, for the purpose of profit. These enterprises operate with a fiduciary duty of generating more energy for themselves (i.e. their owners or shareholders) than they disperse financially. Furthermore, their concept of 'surplus', although sourced ecologically, is defined strictly from a paradigm of financial energy: profit and loss, revenues and expenses.

Established with such a structure, such for-profit enterprises may provide products, services and even environmental contributions. However, their underlying duty dictates that their financial surpluses are directed back to themselves at the end of each financial cycle. The result is an inwards energetic spiral of accumulation that steadily depletes the encompassing ecological and social systems which enable their financial energy.⁷⁷

Such a for-profit spin is in opposition to Earth's pattern. No matter how green-intentioned and no matter how "green" its short-term impacts may seem, the net-effect of a for-profit enterprise is inevitably that of systematic ecological depletion.

To be green, first and foremost, an enterprise must have the foundational intention to be green. In otherwords, it must have a for intention to an ecological contribution, that supercedes any other.

Without both an intention of contributing socially and ecologically an enterprise will be unable to attain anything but a dynamic of systematic ecological depletion.

However, with Earth's example as our guide, the path ahead has never been more clear.

Just as just as the Wet'suwet'en understood human and ecological energy as one, so too must we. And just as a salmon's energetic pattern is embeded deep in its DNA, so too must the Earthen pattern be embodied in the very structure of our keen green enterprises. In particular, a cyclical pattern of directing surplus energy to the benefit of both our fellow humans and our kindred relations: not-for-profit enterprises purposed for the enrichment of our common home. Such a for-Earth structure must be publically declared and accounted for— ensuring that the enterprises's surpluses go towards fulfilling it mandate of ecological contribution

That said, there is yet the question of the precise parameters by which an enterprise may track, disclose and apply its financial surpluses.

As we shall see, the intention of an outwards spiral of energy is only one half of Earth's spiral pattern of enrichment.

There is yet matter of our matter.

Our next Earthen ethic.